Walking the Great Wall’s wild side

Share

Robert Reid is a travel writer based in Portland, Oregon, whose writings have appeared in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He’s been the spokesperson for Lonely Planet, appearing on CNN, NBC’s Today Show and NPR to discuss travel trends. He’s currently the Digital Nomad for National Geographic Traveler.

This is exactly what I wanted. I’m alone on a Chinese mountain, a couple hours north of Beijing, following an unrestored section of the Great Wall of China. After two hours’ of hiking, I’m just 10 minutes short of my goal, a spot on Wohushan Mountain where the Great Wall dead ends atop a gorge. There are no souvenir stands or cable car rides here. Just crumbling ramparts of what’s known as a “wild wall.”

Also I’m terrified.

The steep weedy path before me has dwindled to a few feet wide, tilting downward from the wall to a 1000-foot drop I can’t quite see. Splayed along its edges are leaning poles, remnants of a disappeared barrier that point helplessly up, like shrugged shoulders.

I feel like Jimmy Stewart in Vertigo. It’s too wild. I’m turning back, but first I sit. I fixate on the dirt path below me, then – after catching my breath – reach my phone out to record the weakest selfie of all time.

I love China.

The Great Wall is a household name, yet remains misunderstood by almost everyone. For one thing it’s not a wall, but a series of separate walls built over 20 centuries to keep Mongol invasions at bay. No one’s sure how it adds up (counts start at 4,000 miles) and no one agrees even what really is part of the “wall” versus some stranded fort. Reading about it, I was surprised to learn that Mao once wrote a (bad) poem about it, yet historically China has been less awed by it than visitors from the West, who created the myth that it can be seen from outer space. (It can’t.)

Its impact to the visitor is easier to decipher. Most visitors reach the Wall on daytrips from Beijing, which is surrounded by an arc of Ming-era walls from the 16th century. Most trips hit sections like Badaling or Mutianyu to ride cable cars up to the ramparts, then ride down on toboggan tracks. It’s fun, and busy.

I’ve been before, but this time I wanted space for myself.

It’s not always easy to know where to start. Huanghuacheng or Jinshanling? I plied several guidebooks and the superb Great Wall Forum to read up on options. The latter’s creator Bryan Feldman, who told me via email it’s “too personal” to explain how he, a Wall fanatic, helped me zero in on the Gubeikou area. Some tours go here during peak season. Otherwise you go by bus.

From Beijing’s Dongzhimen bus station, I board an express 980 bus for 15 yuan (about $2.30) to Miyun, where it takes some effort – and a helpful detour by one assisting local – to track down the No. 25 bus stop. Luckily it comes within a few minutes (the buses only run every hour or two). We stop to pick up rural Chinese folks by farms for a couple hours before rolling into Gubeikou.

I start at the Great Wall Box House, a historic accommodation amidst a row of traditional-style guesthouses in the shadow of the Panlongshan wall. The English-speaking owner Joe, or Leo Son, wears roundish black frames and a shaved head, giving him a monkish look. We have tea.

“It’s meaningful living here, very peaceful,” he says about life along the Great Wall. “It’s easy to feel older just living by it.”

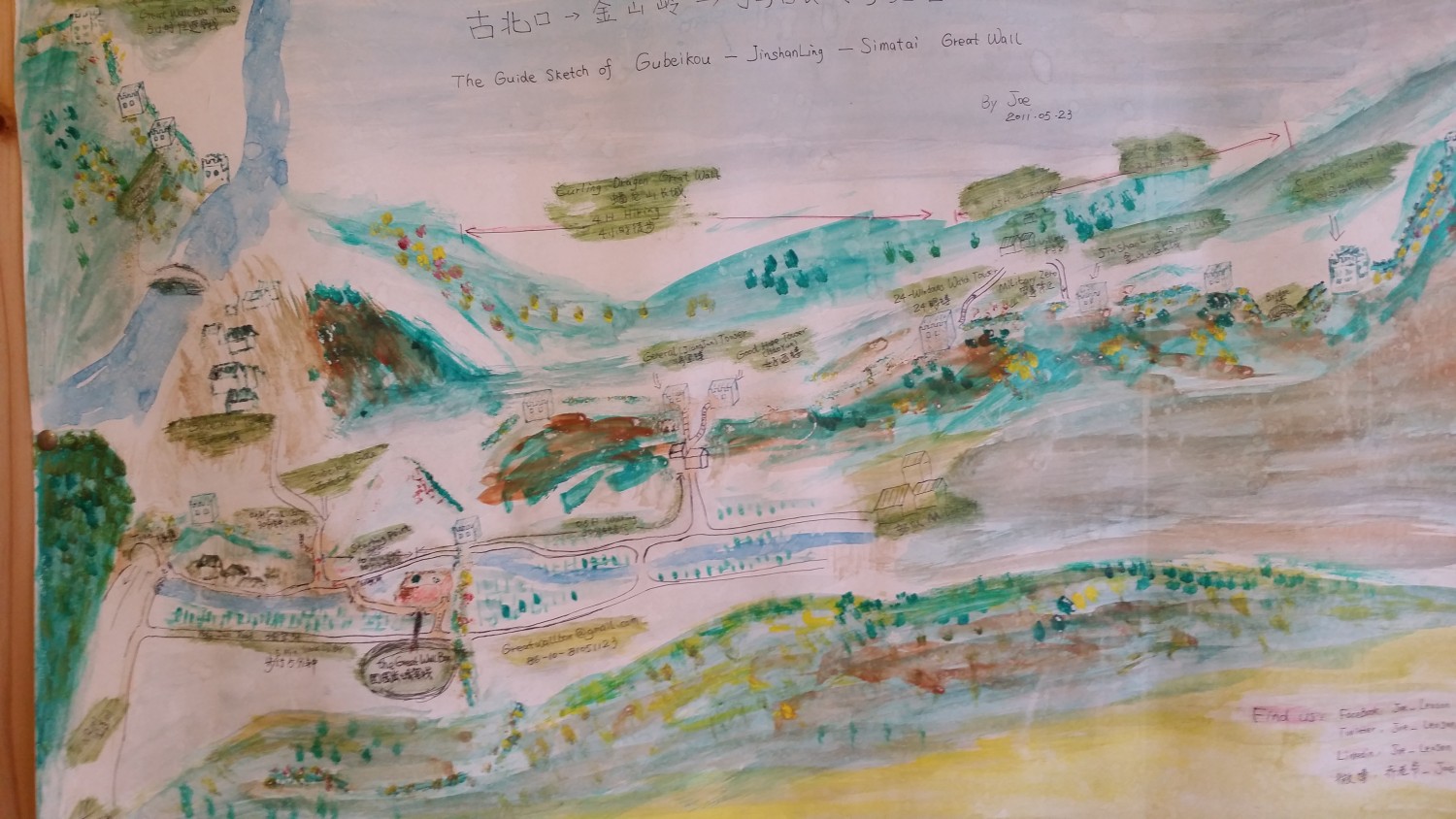

Joe points out some nearby walks for me on a hand-made map on the wall. As I start off on my hike, a voice stops me.

“Can we go too?”

I turn to see a trio of 30-something Chinese women. One holds a phone. She looks at it, then holds up a finger, and repeats her question. I say yes. She taps onto her phone translator a moment, then reads, “Can you wait five minutes?” I can.

And so I’m joined on a three-hour walk with three friends from Guangzhou: Helen, Jessica and Alice, the speaker who hikes in high heels. None have been before, and none really know any English.

We walk through alleys, peeking at village life as men in knit caps ride three-wheel scooters nicknamed “dog-riding rabbits.” A sign leads to a dirt trail that rises up to join the ramparts, which snake up and down between distant towers over a series of misty peaks for miles to come. No one else is in view the whole time.

At one point Helen stops us to pluck a red berry from a wall-side bush to eat. “Suân zao,” she says, or “wild jujube berry” per Alice’s translator. I repeat it and Jessica good-naturedly mocks my accent “shuwan ZAOWWWWW,” the tone of the latter word bending like a question. Helen hands me a few berries to eat and we walk on.

After some minutes, the rise of the walls rise steeper. Helen holds up her phone and plays a Chinese pop-dirge – if that genre exists – on her speaker, giving out an unexpected ambience to the scene. It’s followed by Katy Perry’s “Roar.”

Later, after an all-veggie meal at Joe’s guesthouse, I start a solitary walk up nearby Wohushan, or Crouching Tiger. From town, I look up for a preview of the hike to come. It seems implausibly high, with steep rises and falls as the wall climbs way up the back and head of its namesake “tiger.”

After crossing the Chaohe River, I join the trail through brush until it soon joins the crumbling wall above a riverside tower. Generally the trail sticks to the base of the wall, which leads every kilometer or so to a tower. At points, doorways lead up to the top of the ramparts. I pop up for a look. A steady breeze in the sun hits me, along with a view of a weedy walkway of crumbling rock that seems less secure than Panlongshan. I pause and hear the notes of a Hayden song somehow reaching me from a town piano, now way below me.

Back on the trail below, I’m nearly to the top when I find the trail has squeezed out to the ledge.

“This is as far as I go,” I tell myself making slow certain steps back to the penultimate tower of the hike.

I sit awhile there, the gorge endpoint tantalizing just out of view. I look towards the horizon, counting the number of mountains in a straight line (I get to 15 before losing track). I’ve no regrets stopping my three-hour hike just short of its dramatic finale.

It seems wild enough for me to try a wall like this alone, yet know when to call it a day.

To do this trip

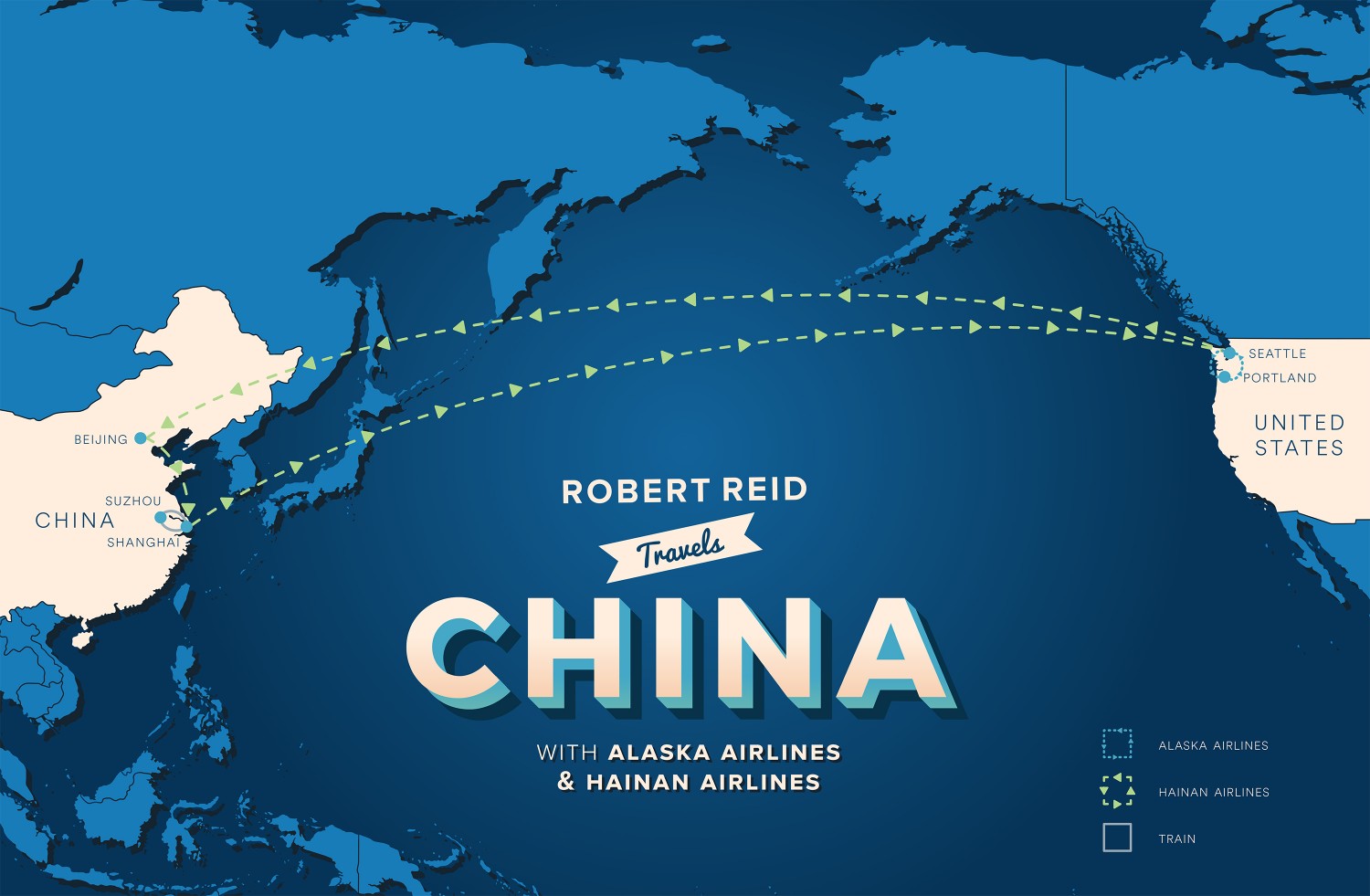

I recently returned from a trip to Shanghai, Suzhou and Beijing, China, on Hainan Airlines, one of Alaska’s newest Mileage Plan partners. Hainan, a China-based, five-star airline, operates nonstop service from Seattle to Bejing and Shanghai and from San Jose, California to Beijing. Hainan also launched nonstop service from Los Angeles to Changsha, Hunan Province Jan. 21, 2016. All of Hainan’s North American routes are flown by Boeing 787 Dreamliners.

Boarding is like immediately stepping into China, beginning with the food. An array of multi-course authentic Chinese meals come — steaming pot stickers in small trays — along with a selection of several Chinese loose leaf teas. Also, all miles flown count toward your Alaska Airlines Mileage Plan account.

On my trip to Beijing, I stayed at the Shangri-La’s China World Summit Wing in Beijing, toasting my trip on the 80th floor bar, the capital’s highest bar.

Great Wall Adventure is a reliable tour company that offers day trips to Gubeikou in non-winter months. To climb both walls in this story, it’s best to overnight at Gubeikou’s China Wall Box House. Its website lists directions on reaching the town by bus.

Follow Reid’s travels online at reidontravel.com and on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.